Tiny Habits

The Small Changes That Change Everything

by BJ Fogg

Buy Book: Print | eBook | Audiobook

Member Downloads:

| Audiobook not playing? → | 🙌 Login › | or | 🔥 Join › |

About

Tiny Habits was written by BJ Fogg, who is the founder of the Behavior Design Lab at Stanford University. He’s one of the world’s foremost experts on the science and psychology of behavior change, and his work in this area has had a significant impact on the way we approach habit change. Whether we’re talking about product development or personal development—if it involves change, BJ Fogg is your guy. And in Tiny Habits, he shares his research-backed insights on habit change and why it doesn’t have to be as hard as you think.

Here’s what you’ll learn about in this book summary:

- The key to creating habits that stick

- How to use the Fogg Behavior Model as a framework for creating the changes you want to see in your life

- How to use formulas to help new habits take hold

- and much, much more..

Tweetable summary

You can start making major changes by taking minor actions. The notion that all change is hard is a myth. In reality, change can be easy if you know the simple steps of behavior design.

Crucial quotes

“If there’s one concept from my book I hope you embrace, it’s this: People change best by feeling good, not by feeling bad.” —BJ Fogg, from Tiny Habits

“…bad habits are not fundamentally different from good habits when it comes to basic components. Behavior is behavior; it’s always a result of motivation, ability, and a prompt coming together at the same moment.” —BJ Fogg, from Tiny Habits

“Once you remove any hint of judgment, your behavior becomes a science experiment. A sense of exploration and discovery is a prerequisite to success, not just an added bonus.” —BJ Fogg, from Tiny Habits

BIG IDEAS

- Tiny Is Mighty

- The Fogg Behavior Model (B = Map)

- Place Your Prompt Above The Action Line

- The Anatomy Of Tiny Habits

- The 7 Steps Of Behavior Design

- Anchor Prompts

- Emotions Create Habits

- Celebrate And Feel The “Shine”

1. TINY IS MIGHTY

It’s likely that you’ve got at least one thing in your life that you’d like to change—most people do. Take a moment to think of that thing you want to change right now…

Would you like to change your diet, and begin eating healthier?

Would you like to change the way you look, by losing weight?

Would you like to change your way of life, by exercising more?

Maybe you want to reduce your stress, or get better sleep. Maybe you’d like to make more money. Maybe you want to become a better parent or partner.

What about your productivity? Are you as effective and efficient as you could be? Or is that an area you’d like to improve as well?

Almost everyone wants to make some kind of change.

But there’s a painful gap between what many people WANT and what many people actually DO.

Most people don’t eat the way they want, look the way they want or feel the way they want. Despite what they want, many people continue to be over-stressed and under-rested. Their finances are not where they want them to be, their relationships are not where they want them to be. They’re not as productive or creative as they want to be.

Why is there such a disconnect between what people want and what people do?

Should people be blaming themselves for not doing the things they know they need to do, in order to see the results they want to see? No.

Should you be shaming yourself if you don’t exercise as often as you want? Should you shame yourself if you don’t get enough work done today? No, and No.

BJ Fogg, the author of Tiny Habits tells us that it’s not your fault if you’re not doing everything you want to do. And it isn’t as hard as you think to create positive changes in your life either.

It’s not you that’s the problem. It’s your approach to change that’s the problem. “It’s a design flaw—not a personal flaw.”

When it comes to change, “tiny is mighty.“

“The essence of Tiny Habits is this: Take a behavior you want, make it tiny, find where it fits naturally in your life, and nurture its growth. If you want to create long-term change, it’s best to start small.”

2. THE FOGG BEHAVIOR MODEL (B = MAP)

“Behavior happens when Motivation & Ability & Prompt converge at the same moment.”

Most people know that if you want to change your life, you’re going to need to change your behaviors.

But what most people don’t know is that there are only three simple variables that drive those behaviors.

ENTER: The Fogg Behavior Model.

The Fogg Behavior Model is the framework you’ll be using to understand and unlock the mystery of how habits take hold. It’ll help you install helpful habits and un-install unhelpful ones.

As Fogg puts it in the book, his Behavior Model “represents the three universal elements of behavior and their relationship to one another. It’s based on principles that show us how these elements work together to drive our every action—from flossing one tooth to running a marathon. Once you understand the Behavior Model, you can analyze why a behavior happened, which means you can stop blaming your behavior on the wrong things (like character and self-discipline, for starters). And you can use my model to design for a change in behavior in yourself and in other people.”

If you want to understand why you do what you do, or don’t do what you know you should do, it’s important to understand the following formula:

B = MAP

BEHAVIOR is the result of our MOTIVATION + ABILITY + PROMPT.

That’s the basis of the Fogg Behavior Model.

B = MAP. A simple formula that can lead to incredible results.

Here’s how its works:

A behavior happens when the three elements of MAP—Motivation, Ability, and Prompt—come together at the same time.

- MOTIVATION (M): Your desire to execute a behavior.

- ABILITY (A): Your capacity to execute a behavior.

- PROMPT (P): Your cue (or trigger) to execute a behavior.

Your Motivation can be either High or Low depending upon your level of desire to create change.

Your Ability can be either High or Low depending upon whether something you want to do is Easy to Do (High) or Hard to Do (Low).

Your Prompt is what triggers you to do (or not do) your desired behavior.

Let’s take two examples with the exact same Behavior goal and run them through this model.

Let’s say you’d like to create the behavior of writing in your journal every morning:

EXAMPLE #1

- BEHAVIOR (B): Write in journal immediately upon rising every morning.

- MOTIVATION (M): High—you really want to make this a habit.

- ABILITY (A): High—taking a few minutes to sit down and write in your journal is Easy to Do, therefore your Ability is High.

- PROMPT (P): Your Motivation is High and your Ability is High, so now all you need is a simple Prompt that triggers you to take action. This might be as simple as keeping a pen and a notebook on your bedside table so that it’s easy to grab and write in each morning.

Now, on the flip side, let’s take the same desired Behavior (of journaling each morning), and tweak the variables a bit:

EXAMPLE #2

- BEHAVIOR (B): Write in journal immediately upon rising every morning.

- MOTIVATION (M): Your Motivation level has decreased to Low—you no longer want to write in your journal every morning.

- ABILITY (A): Your Ability level remains High—since it’s still easy enough to actually write in your journal.

- PROMPT (P): Your Prompt has now been removed altogether—your notebook is now hidden in a drawer instead of placed at your bedside table to see first thing every morning.

Now, let’s compare the aforementioned scenarios, shall we?

Example #1 was setup in such a way that would effectively help you install your desired Behavior.

But Example #2 is a different story…

In the second example, you don’t feel like writing in your journal anymore—so your Motivation is gone. Your Ability level remains the same, since it’s still pretty easy for you to actually write in your journal. But now your notebook is hidden in a drawer, which means your Prompt—which reminds you to execute the Behavior—is gone…

Now that we’ve decreased your Motivation and removed your Prompt, how likely are you to do the Behavior of journaling every morning? Not very.

Two things to remember here:

1: “A behavior happens when the three elements of MAP—Motivation, Ability, and Prompt—come together at the same moment. Motivation is your desire to do the behavior. Ability is your capacity to do the behavior. And prompt is your cue to do the behavior.”

2: “You can disrupt a behavior you don’t want by removing the prompt. This isn’t always easy, but removing the prompt is your best first move to stop a behavior from happening.”

B = MAP. It’s a simple formula that applies to ALL human behavior—and it can become a catalyst for change if you use it. And that’s great news, because you can run any and all behaviors through this model. You can use it to create new habits, and you can use it to break habits you want to get rid of.

Actionable insight:

Try running one of your own Behaviors through the Fogg Behavior Model: B = MAP

- BEHAVIOR (B):

- MOTIVATION (M):

- ABILITY (A):

- PROMPT (P):

3. PLACE YOUR PROMPT ABOVE THE ACTION LINE

“When a behavior is prompted above the Action Line, it happens.” —BJ Fogg, Tiny Habits

In the last Big Idea, you learned about how B = MAP: Behavior happens when Motivation + Ability + Prompt come together at the same time.

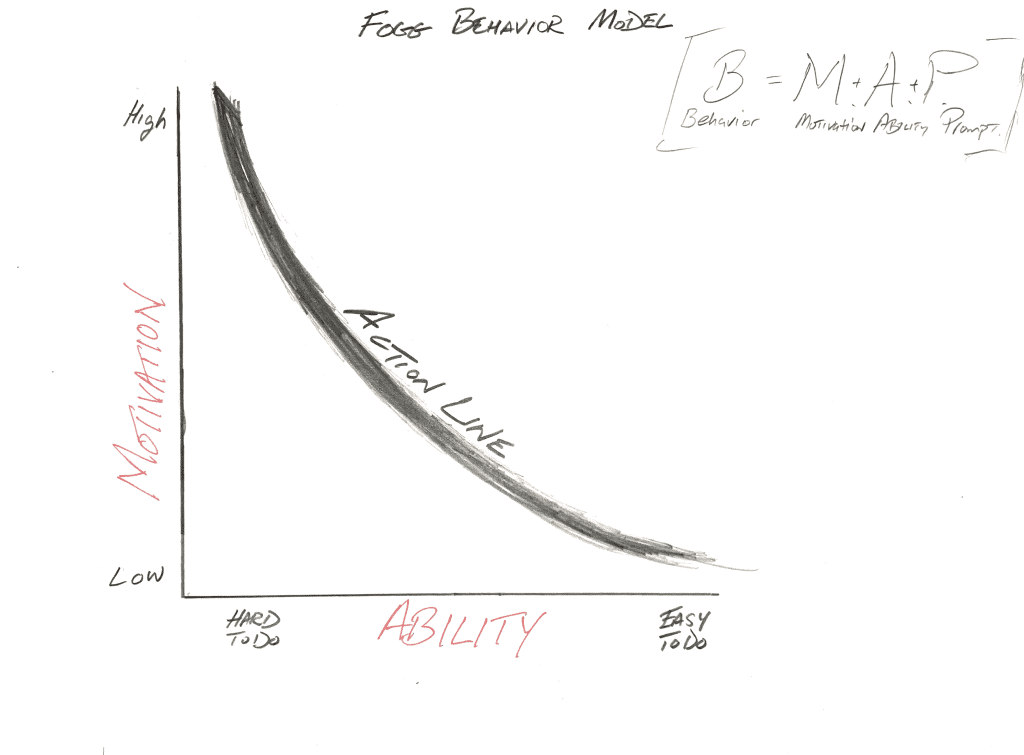

In the book, BJ provides us with a simple graph to drive this idea home.

Here’s what it looks like:

Let’s take a quick moment to break this graph down:

First, along the vertical axis, we’ve got Motivation (M)—which can be High or Low.

Next, along the horizontal axis, we’ve got Ability (A)—which can be Hard to do or Easy to do…

And finally, we have our Prompt (P), which lands either above or below a curved plotline on the graph, which is called the “Action Line.”

The position of your Prompt in relation to the Action Line is crucial because it determines whether you’ll do a Behavior (B) or not.

– If your Motivation is High and your Ability is High (meaning it’s Easy to Do), your Prompt lands ABOVE the Action Line. This is as good as it gets, which means your chances of doing your desired Behavior are high. (Success!)

– If Motivation is Low and Ability is Low (making it Hard to Do), then your Prompt lands BELOW the Action Line. This means your chances of doing your desired Behavior are slim to none.

As BJ puts it: “When a behavior is prompted above the Action Line, it happens. Suppose you have high motivation but no ability (you weigh 120 pounds, but you want to bench-press 500 pounds). You’re going to fall below the Action Line and feel frustrated when you are prompted. On the other hand, if you are capable of the behavior but have zero motivation, a prompt won’t get you to do the behavior; it will only be an annoyance. What causes the behavior to be above or below the line is a combination of motivation pushing up and ability moving you to the right. Here’s a key insight: Behaviors that ultimately become habits will reliably fall above the Action Line.”

I broke this idea down for some of my staff recently with an example of a habit I was working to break:

“When I’m doing Deep Work that requires deep concentration, I’m often tempted to check my phone and order something on Amazon, or quickly reply to emails or texts. This would break my focus and prevent me from doing my best work. So, here’s what I did break this behavior:

The Behavior I want is to focus on doing Deep Work for three-hour blocks of time, uninterrupted, and at least once a day.

My Motivation to check my phone when it buzzed was somewhat high on a moment to moment basis. But this would break my concentration. And, I knew that on a deeper level, my motivation to do Deep Work—to bring my best self to work—was far higher than checking my phone every now and then…

But it was still too easy to fall into the ‘let me check my phone real quick’ trap.

So, how’d I fix this problem?

I adjusted my Ability to check my phone by removing the Prompt altogether.

My Ability level used to be at Easy to Do, because my phone was always on my desk or in my pocket while I worked. This Prompted me to check it whenever I glanced over at it or felt it vibrate in my pocket.

So, I removed the Prompt, by taking my phone, putting it on “Do Not Disturb“ mode, walking it over to my other office down the hall, and then placing it inside my desk drawer.

Now that I’ve removed my Prompt, it’s way harder for me to check my phone every time I get the urge to do so, and way easier for me to stay focused on my work. When I had my phone nearby, it served as a Prompt that landed below the Action Line. Now that I’ve eliminated that Prompt, I know I can reliably dive into my work and develop the habit of working deeply for at least one three-hour time block each day.”

4. THE ANATOMY OF TINY HABITS

“The easier a behavior is to do, the more likely the behavior will become a habit. This applies to habits we consider ‘good’ and ‘bad.’ It doesn’t matter. Behavior is behavior. It all works the same way.” —BJ Fogg, Tiny Habits

Now that we understand that B = MAP, let’s get into the ABC’s of Tiny Habits:

“1. ANCHOR MOMENT

An existing routine (like brushing your teeth) or an event that happens (like a phone ringing). The Anchor Moment reminds you to do the new Tiny Behavior.

2. NEW TINY BEHAVIOR

A simple version of the new habit you want, such as flossing one tooth or doing two push-ups. You do the Tiny Behavior immediately after the Anchor Moment.

3. INSTANT CELEBRATION

Something you do to create positive emotions, such as saying, ‘I did a good job!’ You celebrate immediately after doing the new Tiny Behavior.”

Anchor

Behavior

Celebration.

A. B. C.

Here’s how this might look when you apply it to a real-life scenario…

Let’s say you want to boost your physical strength by exercising more.

You decide that doing push-ups is a great way to increase your strength.

Here’s how you might plug this into the Tiny Habits approach:

ANCHOR MOMENT: After every bathroom visit, you’ll do your new Tiny Behavior…

NEW TINY BEHAVIOR: Instead of exercising for a pre-blocked period of time (like 45 minutes a day), which you’ve tried and failed at in the past, you simplify the behavior and make it super-tiny by planning to do two push-ups every time you take a bathroom break. This makes the behavior too small to fail and puts your Prompt above the Action Line.

CELEBRATION: Each time you crank out your two pushups, celebrate by shouting “AWESOME” or by fist-pumping the air or by silently (but exuberantly) whispering “YES” to yourself. However you do it, take a quick sec to celebrate each time you do a behavior. It goes a long way.

Actionable insight:

- When you design your own Tiny Habits, always remember to make them super tiny. Make them so small it’s impossible to fail: Floss one tooth. Do two pushups. Take two sips of water. File one thing. Respond to one email. Fold just one item from your laundry basket. Clean for just 5 minutes. You get the idea.

5. THE 7 STEPS OF BEHAVIOR DESIGN

“If our attempts to create this habit don’t work, we will troubleshoot, starting with the prompt. And we won’t blame ourselves for lack of motivation or willpower. What we are doing is all about design—and redesign. If we need to tap into willpower, we are doing it wrong. If we revise the prompt and make the behavior as simple as possible, and we still don’t succeed, we’ll back up and pick a different behavior—one that we actually want to do.” —BJ Fogg

In the book, BJ describes the seven key steps in the Behavior Design process. Let’s break each of them down, one by one:

1: Clarify the Aspiration. What do you want to accomplish?

2: Explore Behavior Options. What needs to happen in order for you to accomplish your aspiration?

3: Match with Specific Behaviors. What is it—specifically—that you can do?

4: Start Tiny. Break that behavior down into something so (so) tiny that it feels silly NOT to do it.

5: Find a Good Prompt. Find a good prompt by connecting the behavior to something you’re already doing.

6: Celebrate Successes. Hack your brain’s reward centers by celebrating immediately after you do a behavior. Every action deserves to be celebrated, no matter how tiny.

7: Troubleshoot, Iterate, & Expand. Keep tweaking and adjusting until you find what works. (Perhaps you’re motivated but your prompt is below the action line, preventing you from doing the behavior—in which case, you adjust the prompt and trying again.) Remember: You are NOT the problem. Your approach to change is. It’s a design flaw—not a personal flaw.

6. ANCHOR PROMPTS

“You already have a lot of reliable routines, and each of them can serve as an Action Prompt for a new habit. You put your feet on the floor in the morning. You boil water for tea or turn on the coffee maker. You flush the toilet. You drop your kid off at school. You hang your coat up when you walk through the door at the end of the day. You put your head on a pillow every night.

These actions are already embedded in your life so seamlessly and naturally that you don’t have to think about them. And because of that, they make fantastic prompts. It’s an elegant design solution because it’s so natural. You already have an entire ecosystem of routines humming along nicely—you just have to tap into it.

👋 Hey

You’ll Need a Subscription to Keep Reading or Listening

Still not a member?

Join Here »

Already a member? Login here

Free Course: Intro to The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey • Instructed by Dean Bokhari.

Free Course: Intro to The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey • Instructed by Dean Bokhari.